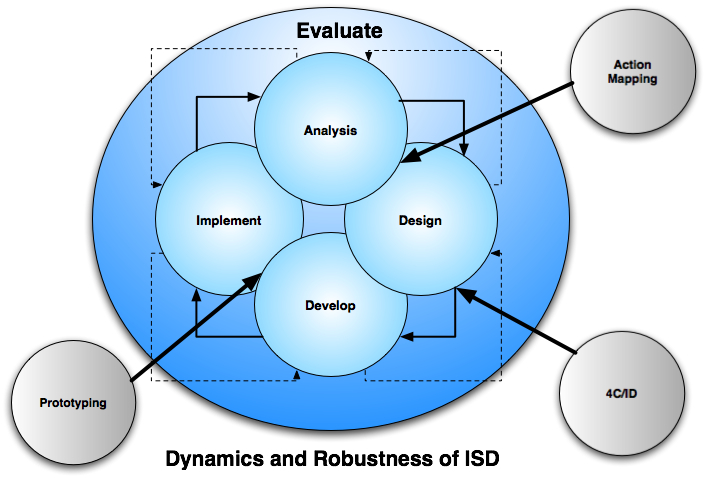

In my last post, The Tools of Our Craft, I wrote how the Four Level Evaluation model is best used by flipping it upside down and that it can be used to evaluate informal and social learning. In this post, I want to expand on the second point—evaluating informal and social learning.

Backwards Planning and Evaluation Model

| 1. Results or Impact - What is our goal? |

| 2. Performance - What must the performers do to achieve the goal? |

| 3. Learning - What must they learn to be able to perform? |

| 4. Reaction - What needs to be done to engage the learners/performers? |

Inherent in the idea of evaluation is “value.” That is, when we evaluate something we are trying to make a judgment about the worth of it. The measurements we obtain gives us information to help base our judgment on. This is the real value of Kirkpatrick's Four Level Evaluation model as it allows us to take a number of measurements throughout the life span of learning process in order to place a value on it, thus it is a process-based solution rather than an event-based solution.

Each stakeholder will normally only use a couple of the levels when making their evaluation, except for the Learning Department. For example, top executives are normally only interested in the first one—Results, as it directly affects the bottom-line. Some are also interested in the last one, Reaction, as they are interested in the engagement aspect—are the employees engaged in their job? Managers and supervisors are normally most interested in the top two levels, Results and Performance, and somewhat in the last one, Reaction. While the Learning Department needs all four to properly deliver and evaluate the learning process.

Note that this post uses as actual problem that is based on informal and social learning for the solution. I wrote about part of it in Strategies for Creating Informal Learning Environments, thus you might want to read the first half of it (you can stop when it comes to the section on OODA).

Results

Implementing a learning process is based on what results or goals you are trying to achieve—and identifying what measurements you need to help evaluate your results will help you to zero in on identify the result or goal you are trying to achieve. For example, saying that you want your employees to quickly find information is normally a poor goal to shoot for as it is hard to measure. Starting with a focused project and then letting demand drive additional initiatives is normally the best way to start implementing social and informal learning processes.

If you find that you are unable to come up with a good measurement, that normally means you have not zeroed in on a viable goal. In that case, use the Japanese method of asking “Why?” five times or until you are able to pinpoint the exact goal you are trying to achieve. Establishing new or improving learning/training processes normally begin with a problem, for example, a manager complains that when he reads the monthly project reports he finds that employees are often faced with the same problems as others and in turn, repeat the same learning process again, thus the same mistakes are repeated throughout the organization.”

“Why?”

“No one realizes that others within the organization have had the same problem before and have normally documented their solution (Lesson Learned).”

“Why?”

“There is no central database for them to look and the people who work next to them are normally unable to help.”

Zeroing in on the actual cause of the problem helps you to build a focused program, in this example, it's a central database for “Lessons Learned” and a means of connecting the people within the organization to see if anyone has been faced with the same problem (and vice versa—allowing people to tweet (broadcast) their problems and their solution that may be of help to others).

In addition, you now have a viable measurement—counting the number of problems/mistakes in the project reports each month to see if they improve.

Performance

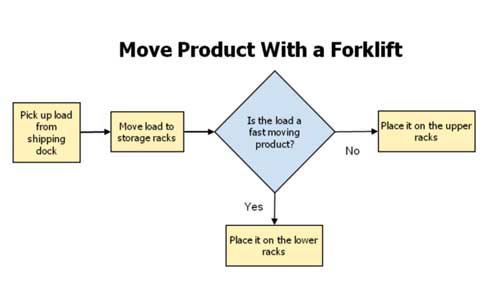

In a normal training situation, performance on the job is normally easily evaluated. For example, when I instructed forklifts operations in a manufacturing plant, after the training/practice period we would assess the learners performing on the forklifts in the actual work environment to ensure they could operate safely and correctly under actual working conditions.

In addition, I used to train users to use Query/400 (a programming language to extract information from a company's computer system). One of the methods we used to assess the performers was that when they returned to their workplace, we required them to build three queries that were assessed by someone from the training department to ensure they could perform on the job. Thus the training is transformed from an event to a process by ensuring their skills are carried over to the workplace.

However, in our working example, it would be hard to observe the entire “Lessons Learned” process as it is a three-prong solution that uses informal and social learning:

- Capture the Lessons Learned by using an After Action Review (AAR)

- Store it in a social site (such as a wiki or SharePoint) for easy retrieval

- Provide a microblogging tool, such as Yammer, to help others to ask about lessons learned that might pertain to their problems and to tweet lessons learned

The first part of the solution could somewhat be evaluated by observing some of the AARs and watching the informal learning taking place as they discuss their problems and solutions, however, the second and third points would be difficult as it would be hard to sit at someone's desk all day to see if they are using the wiki and microblogging tools. While there are probably a number of solutions, one method is to identify approximately how often the social media tools should be used on a daily, weekly or monthly basis and then determine if expectations are being met by counting the number of:

- contributions per month to the wiki (based on their Lessons Learned in the AAR sessions)

- contributions to the microblogging tool (short briefs on their Lessons Learned)

- questions asked on the microblogging tool by employees who could not find a Lesson Learned in the wiki that matched their problem

The approximations are based on the number of problems/mistakes found in the project reports and the total number submitted. You might have to adjust your expectations as the process continues, but it does give you a method for measuring the performance. Note that Tim Wiering has a recent blog post on this method in the Green Chameleon blog.

In addition, once the performers have started using the tools, you can interview them by asking how the new tools are helping them and then capture some of the real success stories, such as videotaping them or using a question and answer interview and then blogging about it. These stories have a two-fold purpose:

- The stories themselves are evidence of the success of the performance solution.

- The stories can be then be used to help other learners/performers to use the new tools in a more effective manner as stories carry a lot of power in a learning process because the learners are able to identify and relate to them.

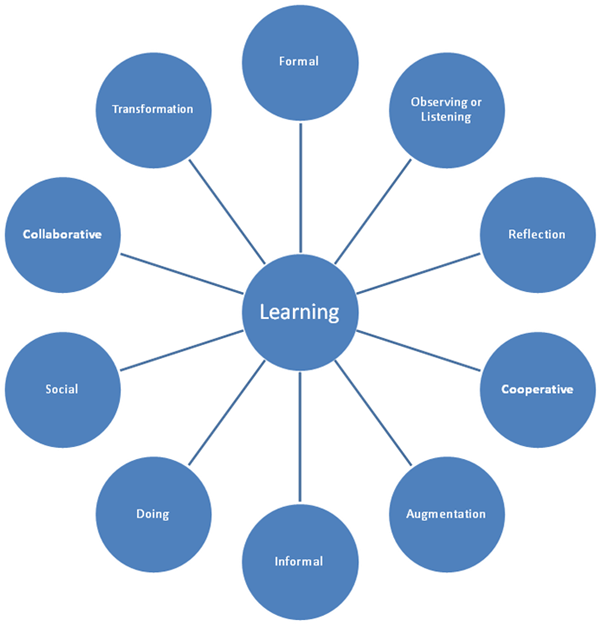

Learning

First, the purpose of this level is not to evaluate what the performers are learning through the AARs, microblogging, and wiki tools when they return to their job (that measurement is captured in the Performance Evaluation), but rather what they need to learn so that they can use the tools on the job. Look around almost any organization and you see processes, programs, tools, etc. that were built on the idea that if we build it, they will come, but are now wastelands because the performers saw no use for them and/or had no real idea how to use them. Just because a tool, such as Yammer or Twitter may be obvious to you, does not mean the intended performers will see a use for it, and for that matter, know how to use it.

In addition, while one organization may not care if someone sends an occasional tweet about the latest Lady Gaga video, another may frown on it, so ensure the intended performers also know what not to use the new tools for.

Since these learning programs can be elearning, classroom, social, informal, etc. and the majority of Learning Designers know how to build and evaluate them, I'm not going to delve into that in this post.

Reaction Engagement

While this may be the last level when flipping Kirkpatrick's Evaluation Model, it is actually the foundation of the other three levels.

One of the mistakes Kirkpatrick made is putting too much emphasis on smiley sheets. As noted in the excellent article, Are You Too Nice to Train?, measuring reaction is mostly a waste of time. What we really want to know is how engaged the learners will be in the learning level and will that engagement carry through to the performance level. People don't care so much about how happy they are with a learning process, but rather how will the new skills and knowledge be of use to them?

For example, when I was stationed in Germany while in the Army we trained on how to protect ourselves and perform during CBR (Chemical/Biological/Radiological) attacks. One of the learning processes was to don our CBR gear (heavy clothing lined with charcoal to absorb the chemical and biological agents, rubber gloves, rubber boots, the full-face rubber protective mask, and of course our helmets to protect our heads) in the midday heat of the summer time and then using a compass and map, move as fast as we could on foot to a given location about two miles away. And I can tell you from experience, this is absolutely no fun at all, yet we learned to do it because no one wants to die from a chemical or biological agent—a ghastly way to go. Thus the training had us totally engaged even though the training was absolutely horrible.

Thus the purpose of this phase is to ensure the learner's are on board with the learning and performance process, which is often best accomplished by ensuring a portion of them and their managers are included in the planning process. You need the managers to help ensure they are on board as employees most often do what their managers emphasize (unless you have some strong informal leaders among them).

Reversing the Process

By using the four levels to build the learning/performance process (going through levels 1 to 4 in the chart below), it is now relative easy to evaluate the program by reversing the process (going through the levels in reverse order [4, 3, 2, 1]:

| Evaluation Level |

Create |

Measurement/

|

| 1. Results or Impact - What is our goal?

| Implement a process that allows the employees to capture Lessons Learned so that others may also learn from them when similar problems arise.

| Reduce number of repeated problems/mistakes in the project reports by 90%. |

| 2. Performance - What must the performers do to achieve the goal?

| Identify and capture “Lessons Learned” in an AAR, post them on a wiki, and tweet them using Yammer.

When problems in their projects arise, they should be able to search the wiki and/or use Yammer to see if there is a previous solution. |

Count the :

- contributions per month to the wiki

- contributions to the microblogging tool

- questions asked on Yammer

Interview performers to capture success stories. |

| 3. Learning - What must they learn to be able to perform?

| Perform an AAR.

Upload the captured “Lessons Learned” to a wiki.

Search and find documents in a wiki that are similar to their problem.

Microblog in Yammer. |

Proficient use of an AAR is measured by using Branching Scenarios in an elearning program and performing an actual AAR in a classroom environment.

The proficient use of the wiki and Yammer are measured in their respective elearning program (multiple choice) and by interacting (social learning) with the instructor and other learners on Yammer. |

| 4. Reaction - What needs to be done to engage the learners/performers?

| Bring learners in on the planning/building process to ensure it meets their needs.

Managers will meet with the learners on a one-on-one basis before they begin the learning process to ensure the program is relevant to their needs.

The instructional staff will meet with the learners during the learning process to ensure it is meeting their needs.

The managers, with help from the learning department, will meet with the performers to ensure the new process is not conflicting with their daily working environment.

|

Learner/performer engagement problems/roadblocks that are encountered will be the first item discussed and solved during the weekly project meetings. |

Since we started with a focused project, we can now let demand drive additional initiatives that expand upon the present social and informal learning platform.

How do you build and measure learning processes?